Editor's Choice

The Food and Drink in History team pick some of their highlights from the collection.

"[T]he Nation's housekeeper": Rationing in the First World War

Emma Woodcock

So many of the documents in this resource celebrate the endless possibilities of food and drink, and therefore hold at their centre the notion of food as always plentiful, dependable, and part of daily life. What happens, then, when food becomes scarce? The WWI Food Governance and Rationing collection from The National Archives provides a fascinating insight into the government's response when food supplies began to dwindle as the war advanced. The Memoranda on National Rationing by the Food Controller explains how and why compulsory rationing was introduced in 1918, stating that "the Food Controller was the Nation's housekeeper at a time when the National larder was considerably under-stocked, and he had to try to make things go round". It explains the logistics behind rationing, lessons learnt from other nations' past methods of controlling food and how the British government's strategy evolved over time, from first being "faced with the phenomenon of the queue" to the post-war period. Other documents in the collection show how the government negotiated the challenges of ensuring equal supplies of food across the country to meet different needs – supplying Kosher food to Jewish populations, higher quantities of food to manual labourers, specific foodstuffs for invalids, adequate milk supplies to children and mothers and comparing the nutritional value of Allied soldiers' rations to those of the Central Powers.

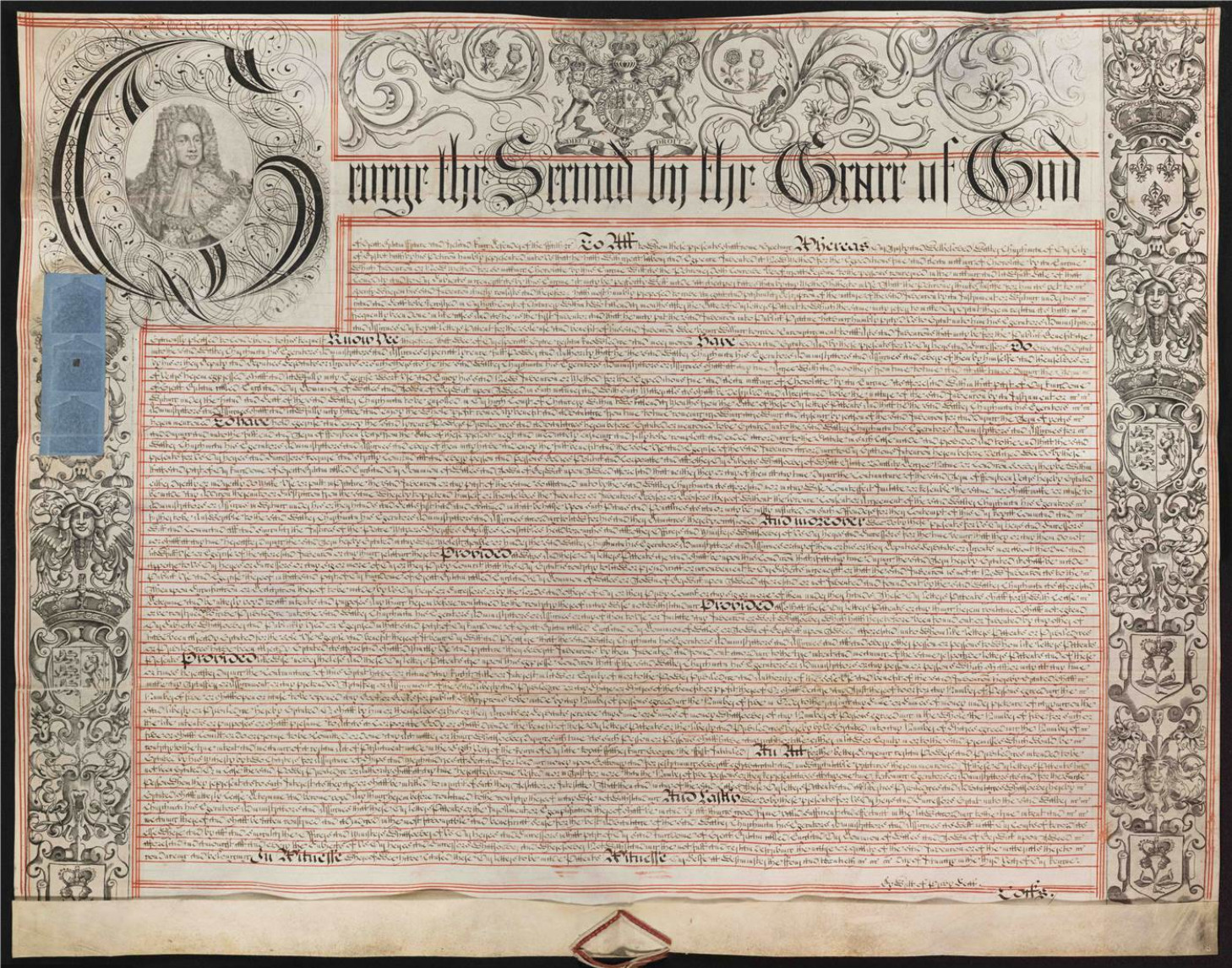

Different documents elaborate on schemes to control the production and equal distribution of key commodities – bread, sugar, meat, butter, cheese and, of course, tea. A selection of government documents and reports detail the development and implementation of the ‘Potatoes in Bread' campaign, which hoped to preserve cereal stocks by encouraging bakers to incorporate mashed potato into their bread. Potatoes: baking tests with the addition of 5% potatoes to flour contains different recipe experiments with remarks on how the potato content impacted the final loaf, and Bread (Use of Potatoes) Order, 1918 details the government's attempt to make the substitution compulsory.

With correspondence between government officials, reports, meetings of minutes and ration books, the collection provides a unique insight into the impact of global politics and conflict on the production, distribution and consumption of food in the United Kingdom and abroad, and into the "extraordinarily successful effort" of the "Nation's housekeeper" to negotiate the crisis and supply the population with food in wartime.

"Ten Nights In A Bar Room": Prohibition and Temperance

Food and Drink in History contains a wealth of items relating to alcohol, encompassing not only its production and consumption but also its regulation in the form of the temperance movement and prohibition. One of the more unusual of these items is Timothy Shay Arthur's Ten Nights in a Bar Room and What I Saw There, arguably the best known and certainly one of the more dramatic temperance novels. Among the many fascinating documents from the University of Michigan is an early edition of this work containing a number of original and striking illustrations. The novel is an intriguing example of the 'Cult of Domesticity'; the prevailing moral value system of the upper and middle classes during the nineteenth century in the United States and United Kingdom. Concern over excessive alcohol consumption began in the United States during the colonial era. As everyday drinking increased in the 1800s, the temperance movement, spearheaded by religious Protestant groups, gathered steam but was halted by the Civil War. In the 1870s however, it returned with a vengeance and developed into a major reform movement. Timothy Shay Arthur's novel became a powerful and popular piece of pro-temperance propaganda.

Food and Drink in History contains a wealth of items relating to alcohol, encompassing not only its production and consumption but also its regulation in the form of the temperance movement and prohibition. One of the more unusual of these items is Timothy Shay Arthur's Ten Nights in a Bar Room and What I Saw There, arguably the best known and certainly one of the more dramatic temperance novels. Among the many fascinating documents from the University of Michigan is an early edition of this work containing a number of original and striking illustrations. The novel is an intriguing example of the 'Cult of Domesticity'; the prevailing moral value system of the upper and middle classes during the nineteenth century in the United States and United Kingdom. Concern over excessive alcohol consumption began in the United States during the colonial era. As everyday drinking increased in the 1800s, the temperance movement, spearheaded by religious Protestant groups, gathered steam but was halted by the Civil War. In the 1870s however, it returned with a vengeance and developed into a major reform movement. Timothy Shay Arthur's novel became a powerful and popular piece of pro-temperance propaganda.

The novel tells the story of the unnamed narrator who, across a number of years, spends ten nights in the 'Sickle and Sheaf' in Cedarville. Here, he witnesses the slow ruin of a number of characters, culminating in the death of the Landlord, Simon Slade, at the hands of his son, Frank. In typical melodramatic fashion, the novel features a slew of villainous characters, no more so than the evil Harvey Green who uses alcohol and gambling to corrupt the young and promising Willy Hammond. The novel also includes several heart-breaking moments, such as when a drunken man is confronted by his daughter begging him to go home and later on when that same child is hit by a thrown glass. The narrator acts as the moral voice, soliloquising on the dangers of drinking and possible solutions. Ultimately, in the novel's closing chapters, the town turns on the 'Sickle and Sheaf' and a series of resolutions result in the destruction of all alcohol on the premises.

Extremely popular upon release, Ten Nights in a Bar Room was adapted for the stage in 1858 (a mere four years after its initial publication) and proved an extremely popular form of pro-prohibition propaganda. It was adapted for the screen several times including in 1910, 1913 and 1921 but most famously in 1931, as a notorious "pre-code" film. Ten Nights in a Bar Room is a fascinating example of the kind of temperance and prohibition-based material released during this period, one of many examples included within Food and Drink in History.

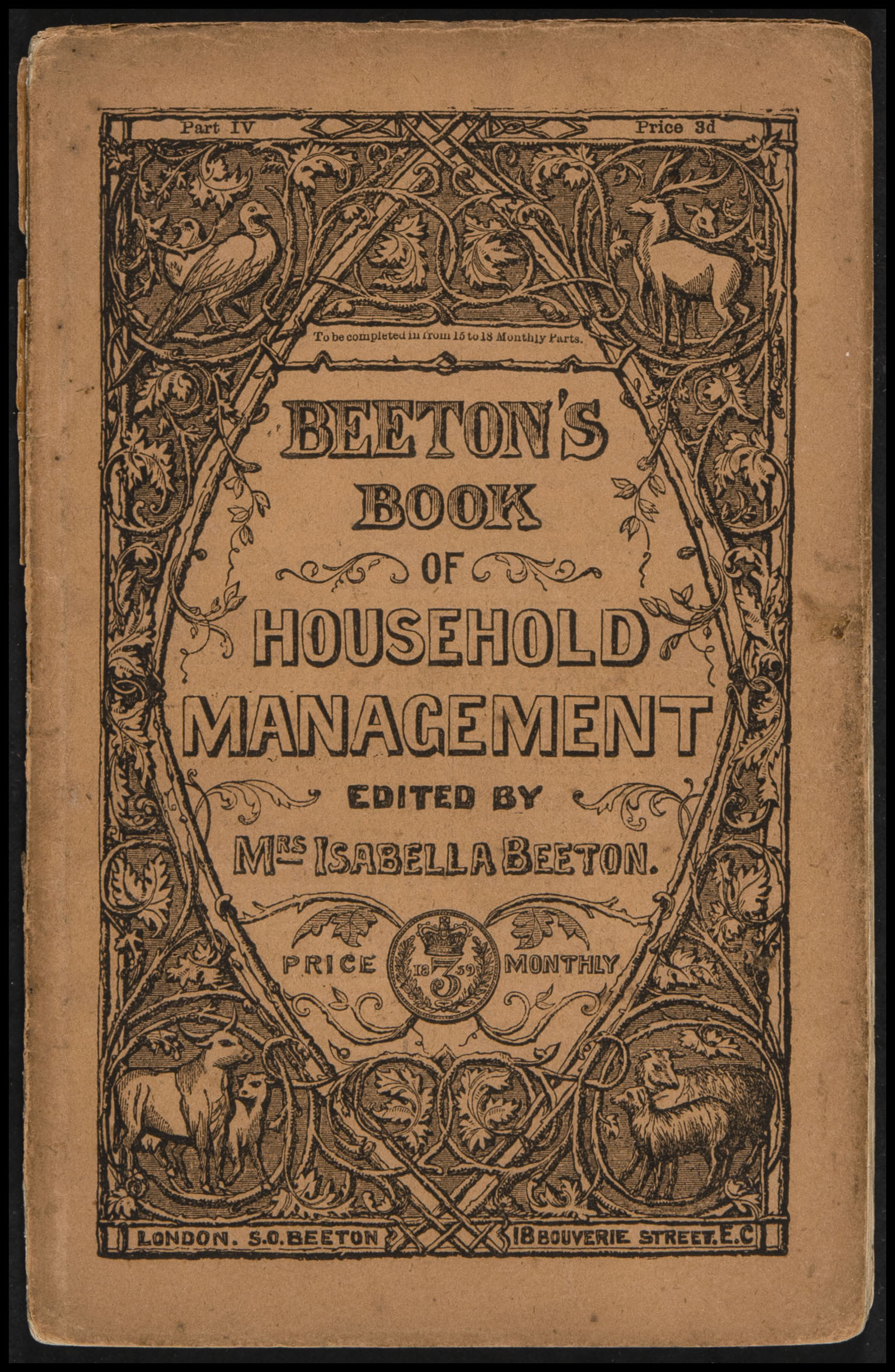

Mrs Beeton's serialised Book of Household Management

Over one hundred and fifty years since its first appearance in print, Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management remains an archetypal text in the field of domestic and culinary arts, not simply for its extensive recipes and household management tips, but also for its creation of a persona of domestic excellence that persists, albeit in different guises, to this day. Through numerous re-editions, the Book of Household Management and the indomitable manufactured identity of "Mrs Beeton" has endured across three centuries.

Over one hundred and fifty years since its first appearance in print, Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management remains an archetypal text in the field of domestic and culinary arts, not simply for its extensive recipes and household management tips, but also for its creation of a persona of domestic excellence that persists, albeit in different guises, to this day. Through numerous re-editions, the Book of Household Management and the indomitable manufactured identity of "Mrs Beeton" has endured across three centuries.Regimentation, structure and organisation are the stalwarts of this domestic ideal; something also reflected in the very presentation of these instalments. Hundreds of recipes are featured within the monthly parts, all organised into sections such as "Soups", "Fish", "Beef" and "Game". As many historians have noted, Beeton's text is significant as one of the first to clearly set out each recipe with a list of ingredients and specific measurements, followed by "mode", or method, and timings. Some recipes even include notes on the history or significance of a particular ingredient: the "Bengal recipe for making mango cheteny [sic]", for example, includes information on the garlic plant and its introduction to England in 1548, whilst "To Cure Tongues" includes a note on the biological and culinary uses of "tongues of animals".

Many of the key themes in Food and Drink in History are inherent in this rich publication, from food and identity to food and gender, economics, production, preparation and politics. To find out more about the history of Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management, listen to Adventures in Gastronomy: Mrs Beeton's Cookbook or explore the contextual feature ‘Food Through Time: United Kingdom'.

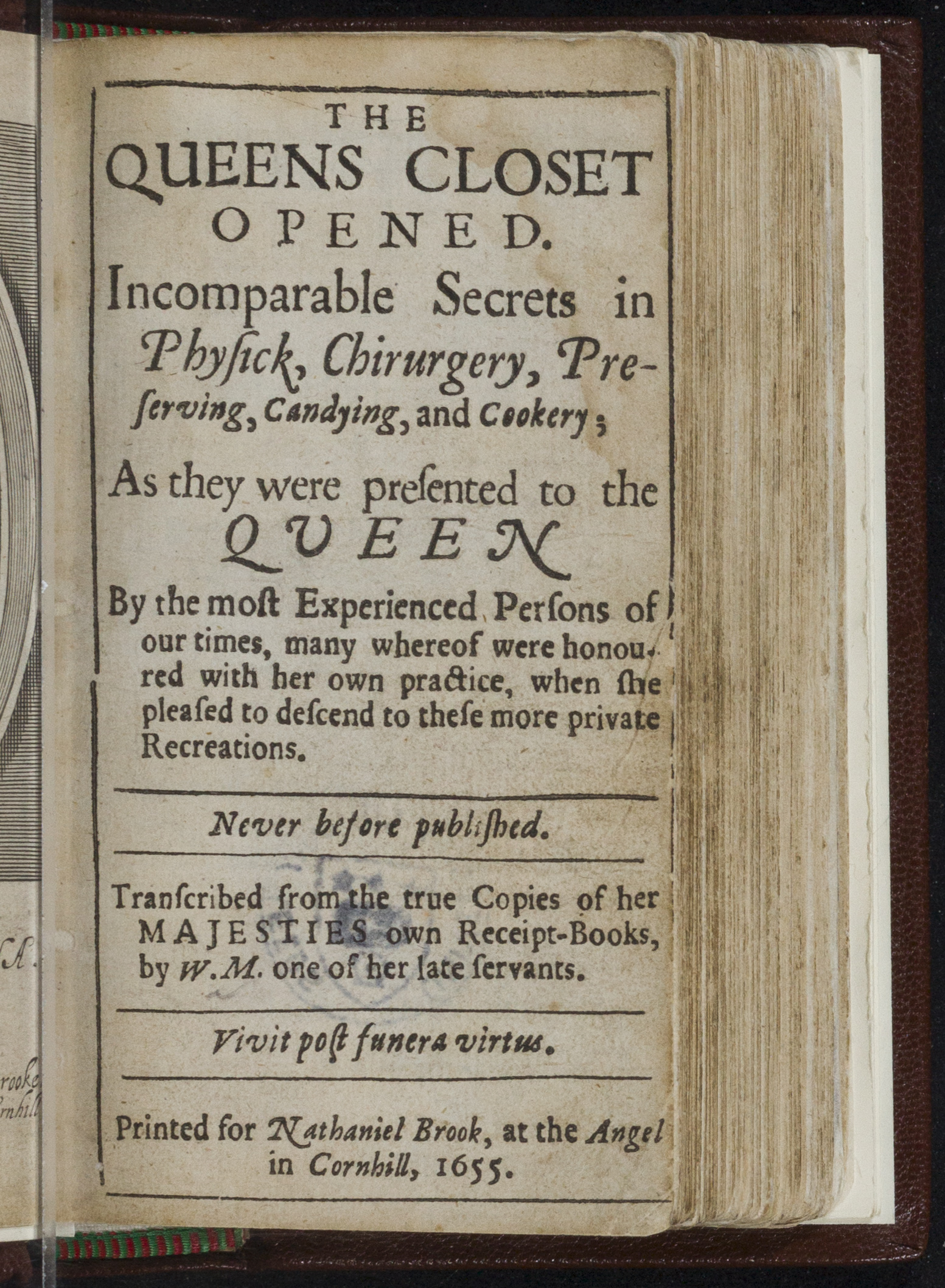

Kitchen Cunning: Early Modern Medicine as Culinary Art

Lauren Clinch

In the 21st century, the phrase “home remedies” carries a certain stigma; it might evoke mental images of cheaply packaged turmeric capsules from eBay, or the times your mother forced you to gargle warm salt water for your cough. Western healthcare systems have evolved to a point where we tend to shun the creation of our own medicines, or even the use of anything that wasn’t prescribed by a certified healthcare professional. But many of the pharmaceutical medicines we rely upon today have roots in centuries-old household remedies, the evidence of which can be found in archives everywhere.

In the 21st century, the phrase “home remedies” carries a certain stigma; it might evoke mental images of cheaply packaged turmeric capsules from eBay, or the times your mother forced you to gargle warm salt water for your cough. Western healthcare systems have evolved to a point where we tend to shun the creation of our own medicines, or even the use of anything that wasn’t prescribed by a certified healthcare professional. But many of the pharmaceutical medicines we rely upon today have roots in centuries-old household remedies, the evidence of which can be found in archives everywhere.The J S Fry & Sons collection

Emma Woodcock

The J S Fry & Sons collection from Bristol City Archives stands out as a highlight within Module 2 of Food and Drink in History. It provides a cross-section of the workings of the brand throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, from inventories of its Bristol factories to promotional material and sales figures.

The documents in this collection encompass the whole system of chocolate manufacturing. The Purchasing Contract Books record contract information from 1883 to 1918 relating to a range of commodities including cocoa, molasses, almonds and glucose, documenting fluctuations in price and quality, as well as often the ship upon which they were transported and comments on quality. Alongside these, one can also study the Cocoa Stocks from 1902-1919, where the company organised its stocks by place of origin. These documents, with others in the collection, facilitate wider studies of the cocoa trade across the globe.

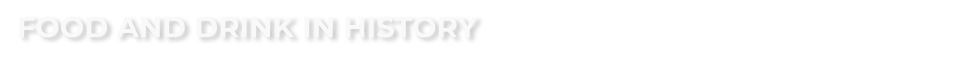

In including the Letters Patent to Walter Churchman, the collection traces Fry’s to its origins. Churchman was the apothecary from whom Joseph Fry and John Vaughan purchased a small shop in 1761 and, with it, the patent for a chocolate refining process, marking the beginnings of a firm which would go on to become the largest commercial producer of chocolate in Britain. In 1847 Fry’s produced the first solid chocolate bar, and the Chocolate Cream became the first mass-produced bar when it was launched in 1866. Behind these huge commercial successes, though, were years of recipe testing and experimentation. The various manuscript recipe books in this collection painstakingly document recipe development from the 1770s until the early twentieth century. Recipe book (1770-1779) includes test recipes with corrections and annotations, as well as the date on which they were used and, in places, the person from whom the recipe originates. Its recipe for vanilla chocolate includes the remark “This was very good when done but think if there had been 8 ounces more of vanilla it would have been rather more perfect”, followed by a comment made a year later which states “on keeping the above chocolate a year it is found to be very fine and to give satisfaction”. Through these recipe books and the other documents in the J S Fry & Sons collection it is possible both to trace changes in recipes and product lines and to gain an insight into the stories of how trial, error and experimentation led to the manufacture of confectionery items still popular today.